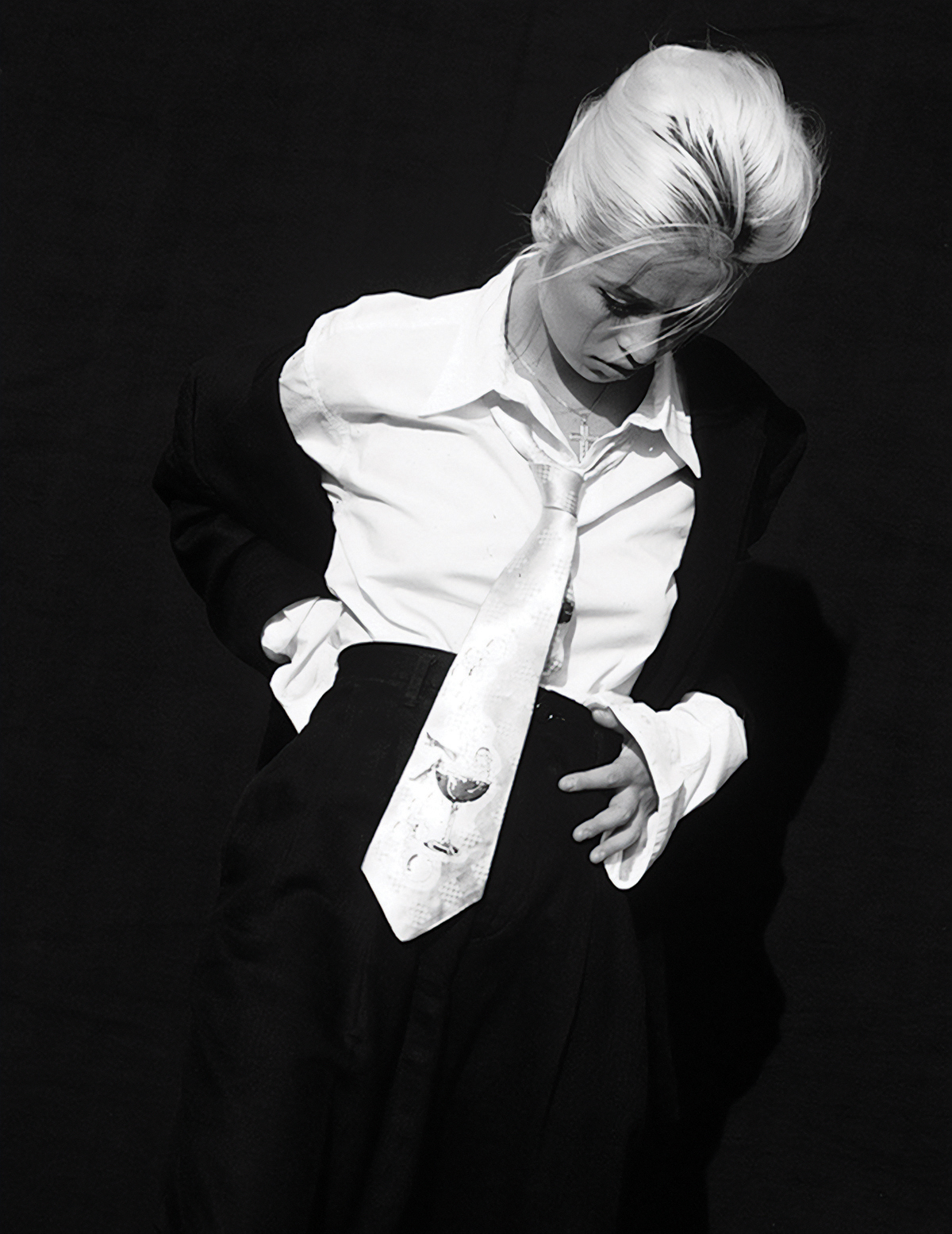

photos courtesy of Wendy James

find more Wendy at thewendyjames.com

Published in Ritsuko 2

Wendy James: I know what it’s like to be your own boss and be self-sufficient. It’s so much work, but then at the end of the day, you do end up with what you wanted.

Ryan Simón: Yes. It is nice that now you can do that, more than ever. A lot of people I talk to are podcasters and, you know, indie DIY artists who have a lot of control over their work, their distribution, all that. Everyone’s kind of their own little Citizen Kane now. Everyone’s their own little media empire.

Wendy: That doesn’t stop one wishing you could hand it off to someone else and just be the artist. Inevitably, if you’re a perfectionist and you start delegating to people who aren’t absolutely the perfect choice — you know, laziness, cutting corners, their decision-making — it can go astray. That is far more painful than having to do the work.

Ryan: Have you found it hard to handle your art as a business? For me, this magazine, it’s still very much a creative endeavor. I’ve had to force myself to be more pragmatic and business-minded in how I approach all this, instead of just focusing on like, Oh, this layout would look cool with this artist. Or, I should go with this theme for the next issue, or whatever.

Wendy: I know what I need to have in place in order for, like, if you need to buy the hard copy of a record, there’s a way for you to do that. I know what I need to have in place to take care of business, but my decisions are completely, sometimes to the detriment of money, they are completely guided by artistic immovability. I can’t budge, if it comes down to sacrificing the integrity of the music. Or the artwork. Or even interviews. All of it. There’s a reason why I have very, very loyal fans, and that’s because for 10 successive albums, particularly after Transvision Vamp and Elvis Costello, I have quality control on everything I do. The strangest, most unlikely people in the strangest, most unlikely places know every single lyric, and you just realize that they are appreciating the details. I don’t know how easy it is to get hugely successful and still have that kind of quality control. Also, on a mass level, I don’t know how many people care. There’s a whole nother world that I’m not really interested in or privy to, you know, where it’s just vocoder and some shitty lyrics, bass and kickdrum. You know?

Ryan: [Laughs.] Yeah, absolutely.

Wendy: And I get that because part of my journey through music, one of the scenes I went through was the rave culture. That’s not exactly based on Bob Dylanesque lyrics, but it was really, really exciting and compulsive.

Ryan: Was that in London?

Wendy: Yes. You go into one of those spaces, and you just immediately start fucking trancing out, man. [Laughs.]

Ryan: Yeah, that’s fun. I like those spaces.

Wendy: I suppose at the end of the day, whether it’s Lou Reed or Bob Dylan or, you know, the ones who are known for their great lyrics, that’s what I like. I like lyrics and I like melody. And, of course, rhythm, but I do like a song with a good melody. Again, I don’t know if anyone’s really writing great melodies anymore. I think people’s ears have changed—

Ryan: Yes.

Wendy: —regarding what they want to hear. What they consider to be a melody. You know, if I’m in a taxi or something, whether it’s indie or pop radio, there’s a pretty unimaginative melody, and they repeat it a thousand times, and I guess it hooks into your brain and satisfies you that that’s a good melody. But a really good melody is the way Lou Reed writes a song. Or, you know, (it’s a bit schmaltzy, but very, very important) Bacharach and David. Or “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough”! Motown! This is back in the days when those guys got their chops being songwriters for other artists. I mean, of course, out there, unknown to me but definitely out there, there’s some teenager, girl or boy, that just has the natural gift for beautiful songwriting. I hope he or she bubbles to the top. But it’s pretty fucking banal and brutal out there now. I mean, I haven’t heard Sabrina Carpenter, but is she good?

Ryan: Sabrina is alright. She’s catchy and just sits in your head like a brain worm, but yeah. “Banal,” like you said.

Wendy: What about Chappell Roan?

Ryan: I have a friend who’s into Chappell, but I’m out of the loop on that one. She seems talented. What you’re saying about ears, I feel the same way about people’s eyes. A lot of what I’m doing now was borne out of my frustration with how everything looks. The way everything is laid out and designed. People are much more aware of this now, how monotone and lifeless everything has become over the past 15 or so years, but for a while it felt like everything suddenly gravitated towards, you know, gray all-caps Helvetica.

Wendy: In defense of Helvetica, Godard’s movie titles. They are the most genius titles.

Ryan: To be honest, I do use a lot of Helvetica-style fonts. [Laughs.] But, yes, often in the Godardian fashion: squares and rectangles of blocky text…

Wendy: Exactly. With the red, white, and blue. In fact, I’m about to go to New York, and there’s a place I always go to called Posteritati, which is on Centre Street. It’s one of those vintage movie poster stores. The designs are phenomenal. I don’t know, in the art world, are movie posters pooh-poohed? Looked down upon as commercial art? I don’t know. But the design is gorgeous. A lot of it comes out of America, from, you know, signs at gas stations. Incredible. Or the fucking pre-Nascar cars, the way they would do them up for rallies. America really had a design peak of wonderfulness.

Ryan: It’s funny you say that because what instigated this interview was a write-up I found on you in Raygun magazine that I posted on Instagram. I love Raygun. Its layouts and sense of design. Every issue is full of, you know, strange, kinetic typography in these beautifully decomposed layouts.

Wendy: What about CREEM Magazine? You remember CREEM?

Ryan: I don’t have any CREEM, but it pops up on my gram time to time. A lot of these mags only exist anymore in the public conscious as Instagram posts.

Wendy: Interview Magazine?

Ryan: Interview is kind of annoying now, but they’ve managed to stay relevant as a print mag, which is cool. I like that. Their emphasis on the interview has definitely influenced my approach to all this.

Wendy: Going back to melody. No Doubt and Gwen Stefani post-No Doubt, pre-whatever her husband is called — you know, when she was doing [sings] hoo hoo! That song where she’s in the black and white, behind the jail bars. “Sweet Escape.” My God, that melody is incredible.

Ryan: I want to get back to your music. I had fun listening to your discography from beginning to end in prep for this, and it does feel like you, as an artist, really take off with your solo career. I mean, you had your first solo record, the Elvis Costello one, but—

Wendy: That was the conduit.

Ryan: That was the conduit, yeah. Racine No.1 feels like the true beginning of Wendy James.

Wendy: That’s right. Geffen wanted me to go on a big tour to promote the Elvis record, but I was halfway through the recording of that album when it started to not quite sit right with me. In an adverse, but positive way, it’s the Elvis experience that gave me absolute clarity that from here on in I would be writing my own words, representing myself, writing my own melodies, for better or worse. And as it turns out, I feel very strongly that I am now an accomplished songwriter.

Ryan: That comes across. I love Racine 1 and 2. I mean, Transvision Vamp and the Elvis record are fun, but, of course, those had outside producers and a whole press circuit around you setting the narrative of who you are. You know, “Wendy James, the Rebel Girl.” That whole thing.

Wendy: When I was with Transvision Vamp and then Elvis, I wasn’t ready. Some people, I guess Paul Simon or Kurt Cobain or something, they were ready from fucking 15 years old, 14 years old. I could definitely sing and I could definitely perform, but I’d never written a song in my life. I wasn’t ready to reach that stage yet. Like all things in life, I had to go through the other stages to get to The Stage.

Ryan: I just got The Face issue with your infamous semi-nude cover shot by Juergen Teller. I was watching an interview yesterday where the interviewer was kind of grilling you about it, holding you accountable for the cover, being like, “What kind of singer would do this? Is it appropriate for a musician to stand half-naked on a magazine cover?” It was kind of absurd.

Wendy: I was friends with Juergen. He lived around the corner from me in West London. But there was something slightly, uhm… what’s the right word… Juergen told me himself… adamant. I was adamant — and I was — I was so adamant to wear that pearl Thierry Mugler showgirl bra, which wasn’t really Juergen’s style of photography at that time. I don’t know what campaigns he does now. He does campaigns for all the top fashion houses, but in those days, he was doing very non-makeup, potentially just on the border of 16 years old, potentially younger — you know, he’s got a go-sees book about all the young models who’d knock on his door… Anyway, that’s Juergen’s life. He’s very, very successful. But he was my friend. We’d play chess together, we’d drink beers together. But because I was so adamant to get my hair curled like Mae West and wear that pearl necklace, he said he just decided to be more of a reportage photographer rather than a stylist or fashion photographer, and in a mean kind of way he let me step into that giant pile of shit by myself. [Laughs.] A kind of interesting sociological experiment I think is how he saw it.

Ryan: He sensed it was trouble.

Wendy: Commercially, it did extremely well for The Face. This was before fashion and music really cross-pollinated. In those days, being in a very, very sexist place in the music press and an over-the-top fashion business that tells you everything is fabulous, I walked out of that studio and I saw the rough draft of the magazine, and they’re going, “It’s so beautiful, Wendy. Oh my God, I can’t even bear it,” and you walk out going, Oh wow, that’s really great, isn’t it? And then it hit the fucking streets. The uproar from the music press, the sexist music press. There’s an awful word, before your time I’m sure, that described not-bright women. “Bimbo.” You ever hear of that word?

Ryan: Oh yes.

Wendy: I am an intelligent person, but because of my appearance—

Ryan: They gave you the bimbo label.

Wendy: They labelled me as a fucking bimbo. A disposable bimbo. The other day when The Shape of History got reviewed (I think it was in a French magazine), he said, “Who would’ve thought that she’d still be around after all this time?” He wasn’t saying it in a nice way. “We wrote her off as soon as Transvision Vamp finished. What career could she have possibly had?” He found himself rather surprised being given the assignment to review a record of mine. So, I didn’t provide him with the outcome they expected, which was to be a young popstar and then disappear and become fucking whatever one does after that — certainly not to become a songwriter, a producer, and work with the level of musicians that I now work with. These guys can’t get themselves off their knees for Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds, but my drummer is Nick Cave’s drummer. James Sclavunos. Or that album The Price of the Ticket that I did: Lenny Kaye, James Williamson, Glen Matlock, James Sclavunos, produced by Ivan Julian from Richard Hell and the Voidoids. You know, a who’s fucking who of your best top favorites, bar having a New York girl on it. I had a Stooge. I had a Patti Smith. I had a Sex Pistol. I had a Bad Seed. You know? So, fuck y’all.

Ryan: [Laughs.] I like that. The bimbo thing, that was like a sacrificial rite of the press that ramped up over the decades and I think reached a manic peak in the 2000s, where they’d hype up popstars and then berate them for their celebrity, culminating in, you know, Britney Spears shaving her head. Yeah, you thankfully never fell into that category. Again, that’s very evident with how self-produced Racine No.1 onward feels and how self-assured, how composed you come across as a solo artist. I don’t think the press likes to contend with that.

Wendy: Even some of the female journalists are fucking mean as… mean as I don’t know. [Laughs.] Just so bitchy. So nasty. Whether you’re a man or a woman, you don’t raise yourself up by putting someone else down. You raise yourself up because you have merit and you are good at what you do. That’s not to say you shouldn’t call things out for when they are poisonous or crap or garbage. If you don’t say that, then it just turns into one fake circle jerk, where everyone’s saying, “You’re so amazing!” and then behind each other’s backs, “Oh my God, I hate it.”

Ryan: Definitely. Those two attitudes go hand-in-hand in the circle jerk.

Wendy: That’s why I live, at the moment, after all my New York years (of which, there are 17), I live in rural France up a fucking mountain. [Laughs.] I mean, I’m off to Paris and New York on Tuesday. I need to have regular shots of city life because I am a city girl. But nobody can get me up here on the mountain.

Ryan: I feel that living in Montana. I would like to get to the city more, but it is nice to kind of hide out and be engaged with some level of culture and people for as much as I want to be on my phone or computer.

Wendy: Yes, absolutely. And then you can get on with your work.

Ryan: You can actually get things done out here.

Wendy: I mean, if you’re a teenager, no fucking way should you be living up a mountain. You should be in the fucking city going out every night.

Ryan: Definitely. That’s the time to be messy. You have to be messy for a bit to find yourself. I got a bit of that when I moved to the Bay, near San Jose, for college.

Wendy: This album was mixed in Oakland. The last one was in Berkeley.

Ryan: I read somewhere that you do the track listing in the order in which you write the songs. The title track, “The Shape of History,” doesn’t come until the final song, which made me wonder where your headspace was at entering and leaving this album. Especially with this being your tenth album.

Wendy: My overarching thought was that 10 is a period and a start again, because there will be an album 11 and then off we go again, but thinking no more other than this is an important marker in my life: I’ve reached my tenth album. I always have lyrics ready to go because I’m always watching movies, overhearing conversations, thinking my own thoughts, jotting down little phrases that are intended to inspire me later. Maybe it’s a note to self to go back to that article that Joan Didion wrote or a museum exhibition that I know will trigger me into a thought process. I’ve got those notes on-the-go the whole time, and there’s no plan. The feelings come out representing me at that moment in time. When you look back at the whole album, because I have some kind of overview of it now, you can see that a lot of it is a summation of life lessons, maintaining the kick-against-the-pricks attitude that will never dissipate in me. In fact, in some ways, it’s worse. [Laughs.] But also, it’s kind of talking to oneself and to my fans — I wanted it to be a message to the fans, to say thank you for the time we shared. Because my God, they’ve done the whole bloody journey with me. But I don’t sit down and think, I’ve got to write a thank-you song for the fans. It’s just the way it came out, based on the words that had inspired me. Clearly, I was getting drawn into spaces or literature or inspiration that was about, you know, having a wiser overview. I get it when I read Joan Didion. She’s so kind of clinical about herself. It’s at once deeply intimate, but at the same time she’s doing an operation on herself or on the environment she finds herself in. She’s very unforgiving in examining this thing, and therefore you come away with a very intimate picture of what she’s going through or what she’s witnessing.

Ryan: Maybe because it’s your tenth album and it’s called The Shape of History, I was in a similarly reflective space listening to this. The album has this Proustian quality, where it invokes all these memory associations. Immediately, with the piano on the intro song…

Wendy: That was my Leonard Bernstein moment. With the right budget, I would’ve had a fucking full orchestra and it would’ve been “Rhapsody in Blue” looking over Manhattan, you know? I very luckily had my beautiful piano player though, Dave Sherman.

Ryan: The intro and the outro work so well. The piano is like an inviting cinematic—

Wendy: Yes.

Ryan: —overture, and the outro track, the guitar on “The Shape of History,” has a sort of fun, bar-close send-off feel to it. That [sings] dwent-dwent-dwent guitar riff.

Wendy: I start with Bernstein and end with The B-52’s, basically.

Ryan: There’s a lot of New York on the album, but also some California sunshine throughout.

Wendy: That goes back to Joan Didion. Not directly to her writing, but in the movie version of her book, Play It As It Lays, with Tuesday Weld kind of lost on the freeway, the way Didion describes it is she knew she had to be on the freeway by 9:20 in the morning if she was going to hit the snag at route whatever. It just evokes the enormity of L.A. and the freeways. You know, it’s a fabricated city. The movie really spoke to me, and it tied into my own memories. Transvision Vamp broke out of California, not New York, because we were signed to Universal, so my first experiences of staying for any length of time in America were in Hollywood. And then, at a different time, Topanga. I used to love freeway driving. On one of the songs, I talk about the wild poppies on a Sunday afternoon in a Camaro. A girlfriend of mine, that was her Camaro. She said, “I’ve got to take you to this amazing place.” You drive an hour outside of Los Angeles, you get to the hills, and it’s just yellow-orange from all the wild California poppies. So, that’s a lyric in there. There’s a lyric about when I played The Palace Theatre, which is one of the grand old theaters of Downtown Hollywood. So, it’s a mixture, of course, of my own direct experiences and then what gets evoked to me, particularly through movies but also through literature.

Ryan: Beautiful. You ever do any sampling? You ever think about going hip-hop and messing around with samples?

Wendy: The only sampling I’ve ever done — well, now that you say that, maybe that’s what the eleventh album should be.

Ryan: Yeah, you could make it your Portishead trip-hop album.

Wendy: Wow, yeah. Portishead were good, weren’t they?

Ryan: They’re incredible.

Wendy: And Massive Attack. But from the Racine 1 demos, you’ll hear all my own home samplings of, you know, Apocalypse Now and whatever.

Ryan: Do you have a favorite track from The Shape of History?

Wendy: I have a favorite section. You know when it goes into the 3/4 waltz timing at the end of “This Declaration of Love”? It’s that whole Joan Didion Play It As It Lays vibe, and then also you know when Jay-Z did “Hard Knock Life” using the sample from Annie?

Ryan: Oh yeah.

Wendy: I love that little girl’s voice. I started listening to the musical version and, of course, Jay’s version, and so when I go into the 3/4 at the end of “This Declaration of Love,” my notes to self as a producer and to the band (but mostly to myself because they wouldn’t know what I was talking about) were “now we go hip-hop.” It was more in the style of Annie than Jay-Z but — ooh God, I’m rambling on! But that’s my favorite section. I love the fucking guitar solos on “Step Aside Roadkill.”

Ryan: That’s a fun one.

Wendy: I think perhaps for an overall song, I love “Everything Is Magic.” But then I love “Freedomsville,” as well. I love “Thank You For The Time We Shared” because it’s short and sweet.

Ryan: It is sweet. What comes after The Shape of History? You mentioned an eleventh album…

Wendy: Inevitably, I will write an eleventh album. Even in bed last night, I was saying to myself, “You better make it a good one.” The brain is already ticking. You know, I dream of doing nothing, and then I never do. At a certain point, you’re not doing it for the money. You’re doing it because you can’t not do it.