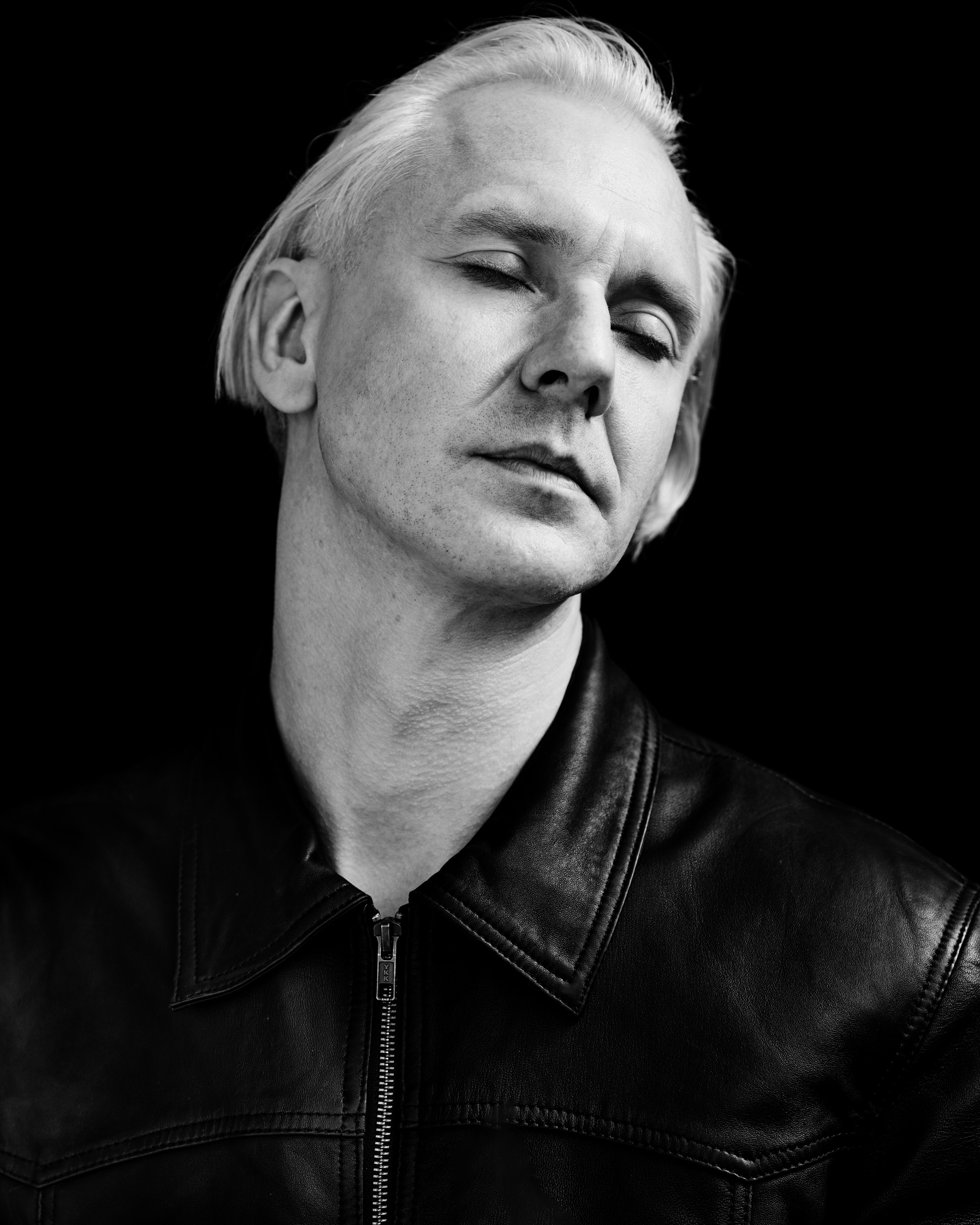

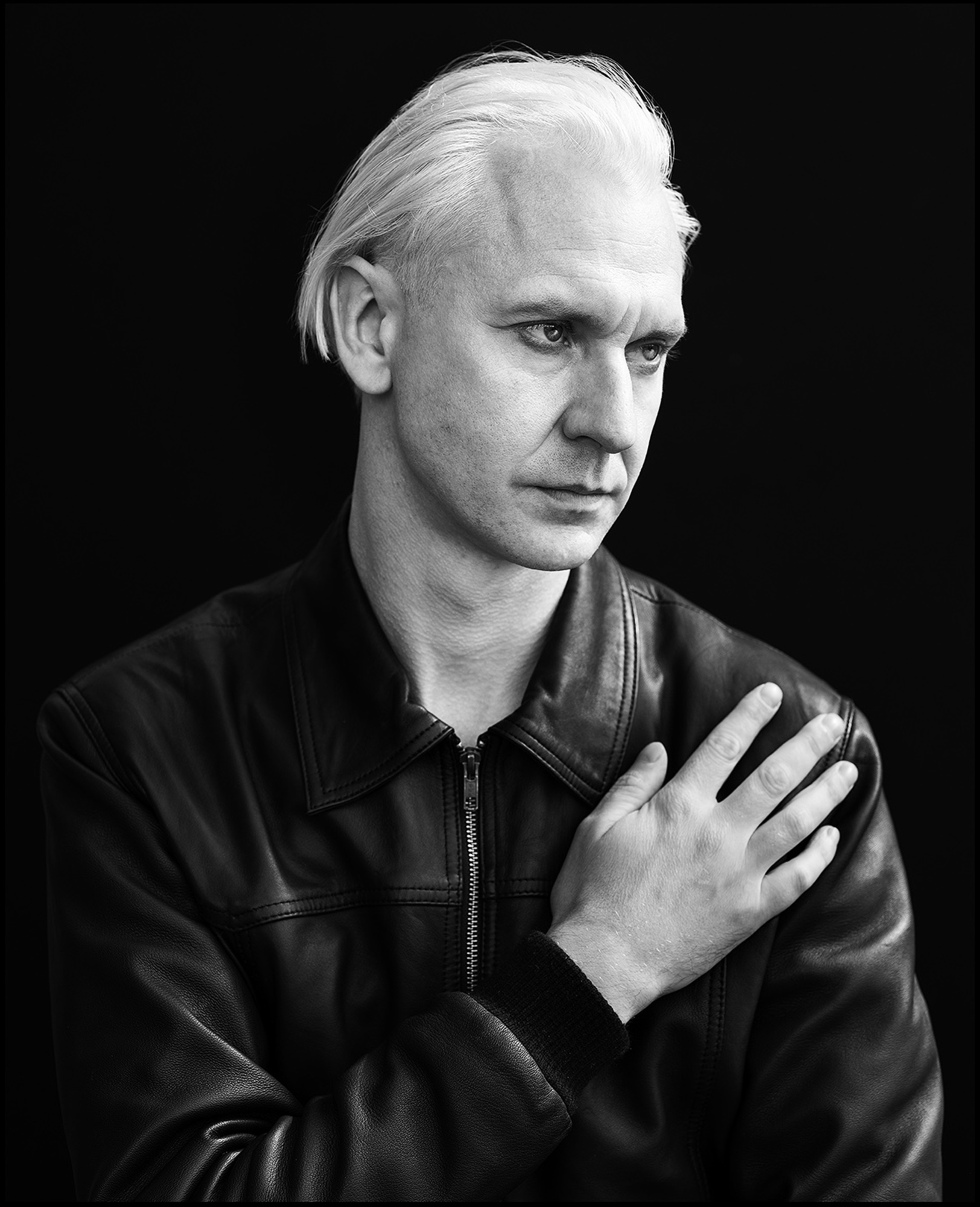

Kieran Leonard — canonized as Saint Leonard after a divine encounter in the California desert — is the visionary writer and musician behind the disquieting, semi-autobiographical novel A Muse (published by the excellent Hyperidean Press) that, as we discuss in this interview, tracks the Odyssean journey of a woman-possessed artist across Europe into the occult undergrowth of California. What’s especially cool about this book is that its central premise, which can be stated as from the muse comes music, affirms the exciting feeling that something more, something truly mystical is at play in his music. Altogether, Leonard’s work has a sense of Place and Presence typically reserved for church, but that Leonard seems to find everywhere.

On that note — Vice Magazine described his latest album, The Golden Hour, as “the reincarnation of David Bowie,” giving it a perfect 10 out of 10. While we agree with the Bowie comparison, our magazine, a magazine of Virtue, drawing its verdicts from a greater authority, is in a unique position to grant The Golden Hour an 11 out of 10.

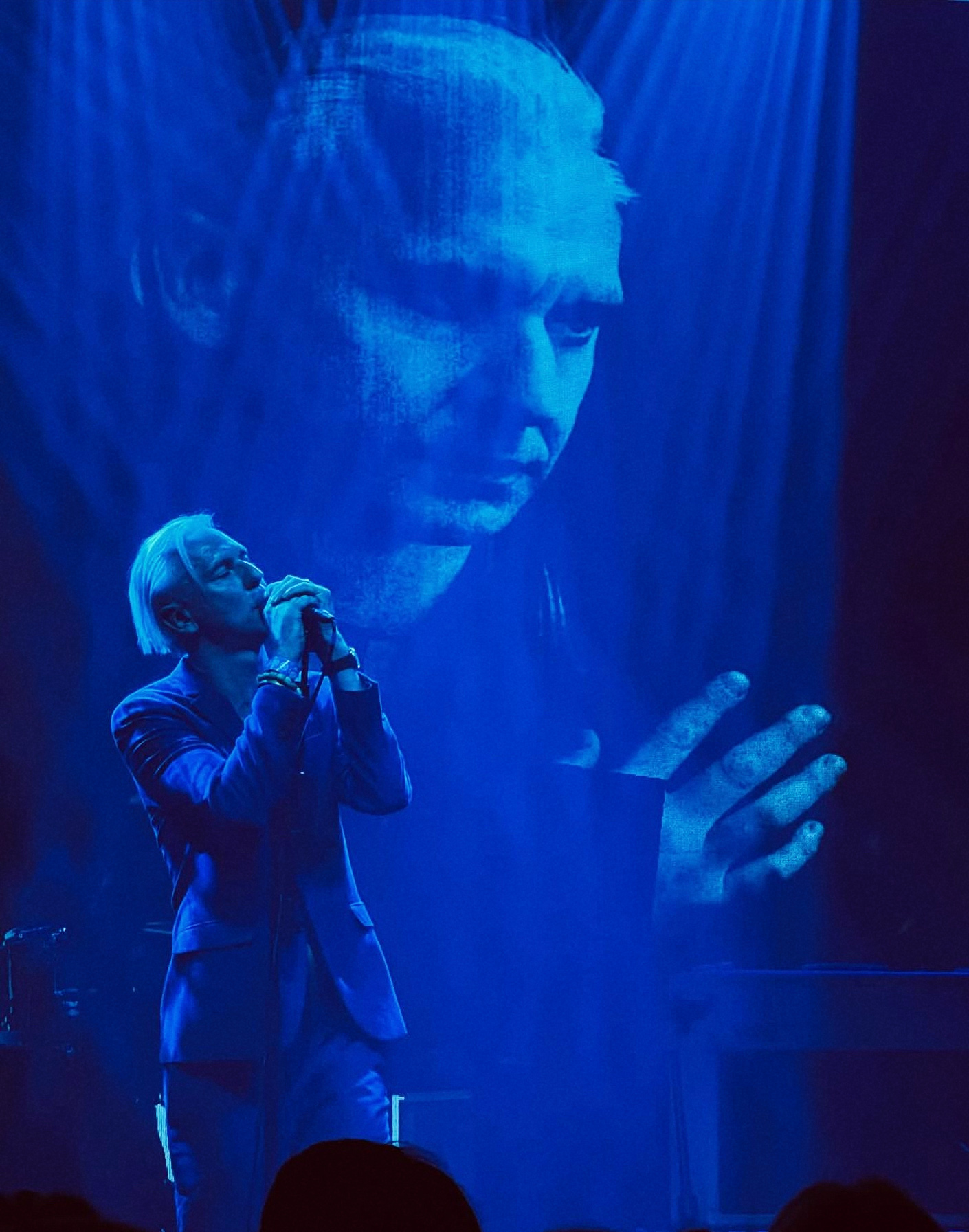

Photos courtesy of Kieran Saint Leonard

Published in Ritsuko 3

Saint Leonard: That Marvin Live we did in London was incredible. It was a spectacular evening. I don’t know how he [Marvin Scott Jarrett] pulled it off actually. The venue that we did it in, KOKO… Legendary. One of the greatest venues in London, so, by definition, one of the greatest venues in the world. He just smashed it. I was like, How is he coordinating all this? He flew from Los Angeles, arrived the night before, and it all came together the night of. I can’t sing his praises enough.

Ryan Simón: That’s cool. That makes me hopeful that Marvin specifically pulled that off because the print magazine hasn’t been a relevant medium since like the ‘90s really. Vice was maybe the last big publication directly involved in youth culture, and even then its print impact was dissolved fairly quickly by the internet. Vice is going back to print though. And Playboy — Playboy is bringing back their print magazine. There was an indie print renaissance during covid that some bigger publications have caught onto too.

Leonard: I know quite a bit about Marvin through being friends with Marvin. He was saying that really it’s a good time to get back into print. There’s suddenly a lot of demand for it again because people have gotten fed up with just everything being on a screen. There is now a market for buying expensive magazines again. Our generation, we remember magazines before the internet, but of course there’s a generation now that has money and that grew up without magazines and that see them as a novelty. They’re like, I want to read a magazine. I want to be in a magazine! It has a cultural cache again. To be honest, I’ve been in a couple issues of Marvin, and I’ve had them around in my house. People open them — not just because I’m in them, by the way — and they’re really like, “Oh my God, I’m enjoying this so much.” So, I would encourage you to keep going with this because certainly in Europe, at least in my bit of the London UK scene, there is definitely an appetite for magazines.

Simón: The internet is still real and important in many ways, but something like a magazine can serve as an anchor, as a point of curation tied to a perspective — the perspective of the editor or team of editors, or whatever. I mean, the upside of the internet is that because there’s virtually no barrier to entry, people can afford to be more experimental and avant-garde in the way they conduct themselves, but… but even then, at the end of the day, you still have to obey certain traditions and forms to be successful.

Leonard: It’s a double-edged sword. I do agree with you that obviously the online thing has promoted experimentation and risk-taking. But I think the great failure of going online is the loss of curation. Curation around music, around any art scene. I really now appreciate that. For example, with the ease of putting music up on Spotify, you get a hundred thousand pieces of music uploaded every day, and (I’m not being a snob, I’m just being fairly direct) that means that 99.9% of it is unlistenable and terrible.

Simón: [Laughs.] Yeah, that’s true. That messes with peoples’ tastes too.

Leonard: Nobody would have paid for it to be recorded. Nobody would have paid to produce it. A record label wouldn’t have signed it, and no one would have backed it to be distributed. We would’ve never heard it. That’s why when my younger fans are like, “Could you imagine what it was like in the ‘70s or even the ‘90s? So much great music.” The thing was to even be heard in the ‘90s, you already passed several hurdles of quality and taste. It just seemed like everything you heard on the radio was really good, but it’s a false idol basically. It’s the process that you miss, not the actual scene.

Simón: Speaking of publishers, we have a link through Hyperidean Press, the publisher of your book. Right before I decided to turn American Vulgaria into a print magazine, I interviewed Adam Lehrer about his book Communions, also published by Hyperidean. The same thing we’re talking about with the internet, I put together the interview and posted it online, and it was so unsatisfying. Just throwing it into a pool of “online writers,” who I really can’t stand. And I loved that interview, so I was like, Well, I want this to at least have some kind of permanent presence somewhere, and that’s when I decided to start a print magazine. Also, I love the idea of people owning the magazine. They’re not just reading an interview or an article to opine about it online. They own it. I’m proud of the magazines I own, like, These are MY magazines, and I loved the idea of creating something people could be proud to own. But yeah, Communions, Hyperidean Press, they helped plant one of the seeds that would turn into this magazine.

Leonard: Hyperidean have such a great presence in the literary scene. In the UK and Europe, they’re kind of the hottest press out there at the moment. I’m not just saying that because my book’s in there. I generally didn’t know that much about them when they approached me after having heard about this book I was working on, A Muse. Everyone I spoke to who was a writer was like, “Oh, they’re brilliant. They’re very daring and put out really good books.” And then I read Communions. It’s just such a small literary world. My new album I made in Berlin with a band called Fat White Family. I met them out in Berlin, we started this collaboration, and it worked out pretty well. But I remember the singer of that band had read Communions, and he’d hand it off. It just did the rounds — everyone was laughing, enjoying Adam’s, you know, exploits.

Simón: Oh yeah.

Leonard: I had forgotten about who published it, and then it was really only when Udith [Dematagoda, Hyperidean’s Editor & Publisher] approached me about publishing my book that I was like, “Oh yes, of course! Communions is on Hyperidean.” That was my memory of it.

Simón: I have about 100 pages left of your book. I’m slow and hungover right now, but I’ve been cruising through it as much as I can today, which has been lovely. It’s been fun to read.

Leonard: Excellent.

Simón: Reading it and listening to your music, I’ve been curious about your background in literature. You seem very bookish. Even in your music, there are references to, you know, Harold Pinter and your single “The Red Book” seems to be a reference to Jung. Were you a bookish kid? Where did your love for literature come from?

Leonard: Absolutely. Where to begin… I do sort of consider myself primarily a writer, even though the main thing I’m known for is being a musician. Writing and literature have been the primary source and influence and motivation behind my making music, hence why on my first record there is “Harold Pinter is Dead” and all the other countless literary allusions. I’m a compulsive bibliophile. For reasons I won’t go into, I had a childhood where I didn’t spend that much time in school, but I was very lucky in terms of having a household full of books, which I consumed at an astonishing rate, frankly. I still do. I read a very, very large amount, sometimes three novels a week.

Simón: Oh man.

Leonard: Yeah, it’s a very big part of my life. I like film and (this sounds funny, I’m not putting this on) I like music, but even though that’s how I make my living, I don’t listen to that much music. I mean, I do listen to music obviously, but the art form I enjoy the absolute most is literature. I couldn’t really define my life without literature, which is quite a strange thing to consider. [Laughs.] But it’s true.

Simón: That’s probably a good thing for your music, having that as your secondary passion to literature. I imagine the music comes easier that way. I used to identify as a writer before I got into all this, and that put too much pressure on my writing.

Leonard: It’s funny you should say that because I work and collaborate with some brilliant musicians, and I’ve realized that they actually find it hard to make music because it is so precious and so important to them. Or they just understand it in such a profound way perhaps. I’m always like, Oh, this is interesting. Or, I should try this. It’s just not precious to me, whereas, to be honest, boy oh boy did I labor over A Muse. I was still editing and doing re-edits after it had gone to print. I was driving Udith insane. He was like, “We’ve printed the first 500 copies. What the hell are you talking about? You can’t change the third word on paragraph 2 on page 367.” I think it’s greatly useful to have your main artistic output be actually your secondary interest.

Simón: Totally. Ever since I — oh, hold up… Your screen is frozen.

[Several minutes later.]

Leonard: Hello, Ryan. Sorry, I don’t know what happened.

Simón: Might be coming from my end. I switched to my phone’s hot spot.

Leonard: Well, we’re back anyways. Where were we?

Simón: Just going off what you were saying, ever since I gave up on being a quote-unquote “writer” and put more of my focus into this magazine, writing has been fun again. It’s good to have at least two different outputs, I’d say.

Leonard: Absolutely. Before I became a musician, I went to drama school. The reason for that was I had been in bands, and I had been writing songs in my late teens, but I really felt that my mum was not very keen on me dropping everything, not having a plan, and just becoming a musician. I knew she would let me go to drama school, and I knew that if I got in, I could do some acting and stuff like that. I suddenly took this slight detour by auditioning for a bunch of London drama schools, and I somehow got into one. I did some acting for a bit. I found it quite interesting, but it was strange. I was doing some bits, some plays, some TV, some film, and I was really getting into studying the craft and taking it seriously, but then I had this realization that I was going to go back to being a musician. Suddenly, for the remaining bit of my acting career, I became much better at acting. It was a really strange thing. So, I would recommend to anyone to have a moment where you put your primary passion on the backburner, try something else out, and see how that works.

Simón: When did the idea of the muse strike you as something you wanted to write about?

Leonard: Wow. That’s funny because I could actually tell you very vividly the exact moment when the idea for the book hit me, somewhat like a thunderbolt. I basically was in the thick of the real event I novelized for the book. I was living in Hollywood, tearing around, trying to make an album, and I had a very, uhm… well, you’ve read the novel: the Higgs character, my long-suffering tour manager — he had moved out to keep an eye on me, and he unfortunately, as you could imagine from reading the book, his role had become primarily driving me around L.A. I remember he was driving me to a Hollywood Hills party, and I’d been drinking that day. I remember just ascending up those serpentine roads up Hollywood Hills, and I had this sudden like, Oh my God, this is a modern-day Olympus. You know, how you leave the lower arena of the mortals and ascend up Mt. Olympus, where these so-called gods and goddesses reside. I thought, Oh, how amusing. My brain literally felt struck by Zeus’ thunderbolt, struck by this thing that’s like, Imagine a muse set in the modern-day, with all the Grecian references and mythological allusions, but set in modern-day America. And as I looked down over L.A., at all the pinpricks of light below me, I thought, Well, that will take me about 10 years to write. But now, here we are. So, I do remember exactly where and when that idea happened. It was one of those ideas that was too surprisingly well-formed and perfect to ignore. In fact, I was speaking to the very wonderful photographer and lady who graces the cover, Emma Tillman. She met me for coffee at the farmers market about three or four months after that. I finished making my album — she’s a great reader, very literary person — and she said, “What’s going to happen? You’ll put the record out, then go on tour?” I was like, “No, I’m actually thinking I’ll just drop everything for a bit and fuck off to a cabin in the woods and write a gothic novel about Grecian muses and idealized versions of mythological worlds in 2015 Los Angeles.” She looked at me and started laughing, and she didn’t stop laughing for about two minutes. I thought, Well, that’s a really good sign.

Simón: The muse thing, especially with how you title the book “a muse,” instead of “the muse” — one of parts where I could feel my mind expanding was that passage that comes fairly early in the book about reality being a simulation within simulations, and how to survive within your simulation, you have to be interesting, or amusing, so that the architect of your simulation doesn’t kill you off. It’s like that South Park episode where the kids discover that all of Earth is just an elaborate TV show for this alien race, who are preparing to “cancel” Earth because they’re bored of the program.

Leonard: I think I attribute that idea to a magazine I’m reading in the book, but I had a couple friends who work in quantum fields and mathematics and whatnot, and that was me quizzing them for hours about how quantum reality actually works. After a night of quite heavy drinking with these very intelligent people, I did come to this sudden realization that’s like, Well, really, if we are in a quantum simulation, the only thing that would keep you alive would be to be entertaining or amusing because it generates novel, experiential data that is useful to them. To be fair, each of these fine minds that worked in those fields couldn’t disprove my hypothesis.

Simón: Totally, it makes sense. That’s such an L.A. epiphany.

Leonard: [Laughs.] Yes, absolutely.

Simón: It’s very Infinite Jest too. A very Foster Wallace idea on amusement and entertainment. But specifically, the way you root “amusement,” in the realm of modern entertainment, to these ancient, pre-conscious impulses towards music I found fascinating. “Amusement” is basically a derogatory word now, meaning like “cheap entertainment” or a “cheap distraction,” instead of, you know, “divine inspiration,” as the word “muse” used to mean. Because it is trippy to think about why we have such an innate, primal pull towards music. Music is, as your book shows, this like occult, alien force that’s in tune with some outer will, even within the, you know, secularized pop music industry.

Leonard: It’s this Dionysian force that comes through us — why do we go back to it, and where is it emerging from?

Simón: Yes, and that it’s released in us as a form of ecstasy. That’s another part of your book I loved, where they discuss how one of the markers of progress in civilization is the increased control and administration of those passions, the passions of raw, Dionysian ecstasy. Which I thought was funny too because in a more literal sense, of all the drugs, ecstasy especially derails me. Everything else, no matter how sloppy I get, I at least feel fundamentally composed, like my moral center is still intact. With ecstasy, I become such a creature. Even if I didn’t do anything, I’ll wake up the next day and just remember my thoughts and desires from the night before, and it’s like [laughs], Wow… Thank God I didn’t act on that impulse.

Leonard: I have a nice cross-reference there. On the new album, The Golden Hour, there’s a track called “Bells & Ecstasy,” and that is based on me and the lads from Fat White Family, while we were in Berlin. Unsurprisingly, various substances were being used during the recording sessions, and they were being applied artistically to solve certain problems. One day, as we were working on a particularly strange piece of music, we all came to the realization that the only two substances that we would never combine are this brand of whiskey called Bell’s, which is terrible, and ecstasy. The combination of those two almost guarantees you become a fool to yourself, however you think you’re behaving. It’s a complete dysregulation of all the senses. We were being completely serious too. These are warlord-level drug takers, these boys, and they’re like, “No no, whiskey and ecstasy combined, all bets are off.” It is pure Dionysian.

Simón: It is. It’s wonderful. [Laughs.] And terrifying. But yeah, the way you articulated that is great. You also have a great sense of place in the book, which is interesting because, in the book and seemingly in your real life, you seem fairly nomadic. The way you identify the ambience of a location, it made me think of this tweet I really liked from a while ago that said something like, “Any place is either haunted or soulless.” That quote kept coming to mind while reading your book because you seem attuned to how certain places are ensouled. Especially given your choices of locations, with the Church of the Horses, the Hecate House — these are mythical locations. I was curious where you think this sense of place comes from.

Leonard: That’s a really nice point and a good question. Thank you. I mean, all the locations in the book are exactly where I was led during the adventures that unfolded. I don’t want to reveal too much about how much is truth and how much is fiction, but all those were places that I visited. That is exactly how the church was. That was exactly the feeling and presence of that place. This is a tangent, but I had a very weird experience: I was playing a solo show 18 months ago in Leeds, and my manager was like, “I fancy a trip. Jump in my car. I’ll drive,” which for Americans is nothing. For English people, a four-hour, five-hour drive is a big deal. I was drinking Jameson, chatting away, and I just dozed off. As I was dozing, he goes, “Oh God, the whole motorway is closed. We have to detour.” Sounds like a horror film scenario. I came to about (I don’t know how long) about 45 minutes later, and as I was looking out the window going, “Oh my God, this is really oddly familiar,” and unbelievably — actually, genuinely very spookily because he had just randomly been taking B roads and side roads and whatnot — before I knew it, we were just on this ancient road leading back to the church. I was like, “What the hell are you doing?” He had no idea, he couldn’t have possibly noticed. I was like, “Stop stop stop,” and he’s like, “What’s wrong?” I was like, “You’re not going to believe this.” He knew about me living in that church. He knew about the book I’ve been writing. I was like, “Somehow, you have accidentally driven us back to the church.” He was like, “Oh my God, what on Earth.” I was like, “We’re back. We’re heading back.” He drove very slowly in a storm up to the church. I was like, “This is just too weird. I’ve falling asleep after a gig, and now you’ve brought me back.” We didn’t go in. I refused to get out of the car.

Simón: Amazing. Yeah, the church isn’t through with you.

Leonard: Sorry, that was a complete tangent. In terms of places… I don’t know. I’ve always traveled a lot. I’ve been peripatetic my whole life. My childhood was very peripatetic. I am really deeply affected by places. I’ve never been able to live or stay anywhere that I wasn’t fascinated by or enthralled by or charmed by. Even in the case of Berlin (I was just thinking about this the other week), I was slightly scared and depressed by it in a very profound way that made me fall in love with Berlin, and I still have that towards Berlin. That’s just an example. It doesn’t have to be particularly beautiful or fascinating — I mean, Berlin is fascinating — or it’s not like I’m only drawn to positive things. A place just has to really grip me, and all the places in the book had done that. They do leave a very indelible print on me. I mean, a lot of the book, for me, was a sort of self-help exercise that well and truly got out of hand in, you know, processing all of these events through writing them down. All those places I felt left a mark or some unfinished business, so in the writing of them, I was revisiting them and trying to process them. It was very fated that I even ended up in a log cabin in Nashville, which could not have been more like Stephen King Evil Dead. Honestly, it’s so funny, Ryan, because I had to try to not lay it on thick in the novel because it really looked like the Evil Dead cabin. I was like, People will think this is ridiculous, if I described it properly. But that’s really what it was: it really was in the woods in the middle of nowhere. I was so lucky to get that place. And then to end up by complete chance at Stanley Kubrick’s house to re-record the record.

Simón: Oh yeah, I read that!

Leonard: It couldn’t have been more charged or prescient for the story I was trying to tell. In a theatrical sense, places are a character in the book. They provide a lot of vatic information about what’s happening to me. It’s funny, that pivotal moment that happens in the book in Vienna when the Pinky character invites me, that is sort of what happened in a way, and Vienna is such a charged location for obvious reasons — so much has happened there, philosophically, socially, historically, musically — so it provides a lot of subtext just by it being the setting.

Simón: This all fits the Odyssean theme of the story too. In a lot of the reviews and mentions of the book, the word “dislocation” comes up a lot, and that’s at the heart of the story of The Odyssey: Odysseus leaves home, and he evades all these episodic traps that try to keep him from coming home. I mean, the story begins with him crying on Calypso’s island because he just wants to go back to his bed and his wife. [Laughs.] The reviewer who — I can’t remember her name, Adam Lehrer mentioned her on your podcast episode — she observed something in your book that’s rarely found in today’s fiction, which is a man’s need not just for affection but for domesticity.

Leonard: Oh yes, I remember Adam talking about this. I thought that was a really smart point he made.

Simón: Yeah, that’s a really relatable part of the book too. To me, this is a very — I’m 34 right now — this is a very end-of-your-twenties book. [Laughs.] You know, because when you leave your twenties, you get over the end of your youth, you get bottled up at home, and suddenly it’s like, Well, I still want to do X, Y, and Z. I still need to keep moving. This magazine has been a way for me to have these sort of Odyssean travels outside of the house, but when I am away, more and more, it’s like, Ah God, who are these freaks? I just want to get home to my family. I need my Penelope.

Leonard: Absolutely. I mean, the idea of the book came quite late in the experiences that formed it, but it really was Odyssean in that way. I took this out of one of the drafts, that I actually didn’t want to leave the church, even though I was desperately unhappy and haunted there. I just knew I had to. I knew that I was going to die there, if I didn’t leave. I was going to just, I don’t know… ossify into the walls of the church. [Laughs.] And then my tour manager, the Higgs character, he’d always reminded me that I basically just wanted to go home for like two-thirds of that tour, until I encountered the Pinky character. Like in The Odyssey, it became apparent that the only way — or no, I think it’s a Joyce line: “My endless journey towards home was in fact home itself.” The idea that the actual journey I went on I would have to accept as my home because there was no going back. The only way was forward. Even by the time I got to Los Angeles, I was like, Well, I really don’t have a home anymore. The church was long gone. My relationship with my fiancé fled. I had been on that journey for about six, seven months by that point, and to be honest, I didn’t stop traveling for two or three years. That’s why at the end of the book, I list all the places where I wrote the book. Which is a nod to Ulysses, the end of Joyce’s Ulysses.

Simón: Oh yeah, yeah. That’s cool.

Leonard: It was actually a significant thing that to really even write the book I had to be constantly moving. I’ve said this to a few close friends now, but it was 10 years really. That night I left the church to go on that tour, I didn’t really stop and settle for 10 years. In my sort of ambition to write an Odyssean tale, I had to have an Odyssean journey, which will take you a decade to complete, with many Medusas and monsters along the way. So, you know, be careful what you wish for.